‘Two Sisters’ by Ngarta, Jukuna, Pat and Eirlys

Kaya everyone, welcome to #DeadlyWABookClub! Over the next three months I’ll be analysing and celebrate the writing of Aboriginal authors from Western Australia. I’ll also be sharing some essays published in the journal JASAL, to raise awareness of the big thinkers of today who are discussing and critiquing Australian literature. This is all thanks to my writer’s fellowship from ASAL/Copyright Agency - thank you! Find out more at ASAL.

‘News came from across the desert, two brothers were on a murderous rampage.’

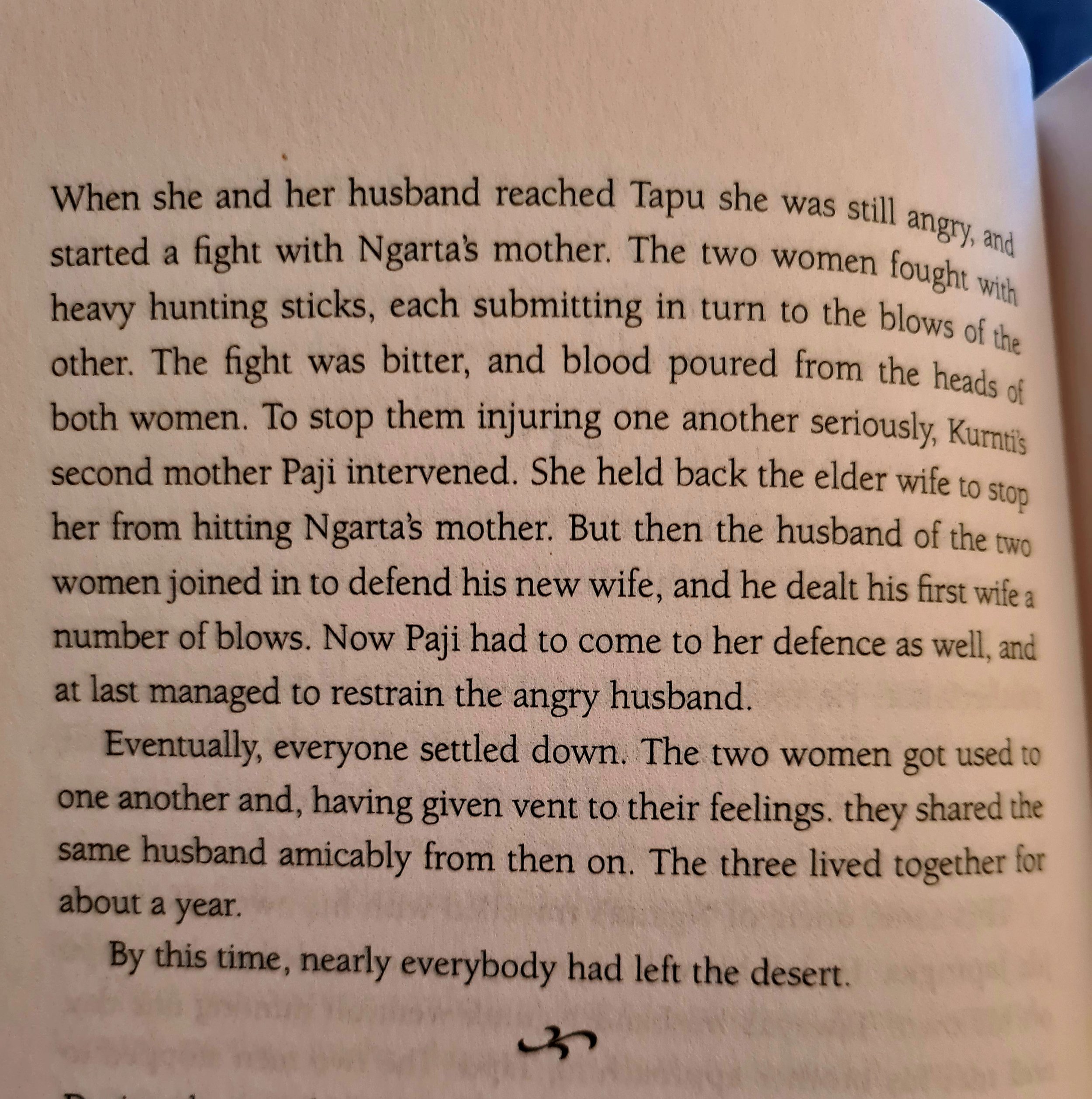

Two Sisters, another hidden Magabala Books gem and written by Ngarta Jinny Bent, Jukuna Mona Chuguna, Pat Lowe and Eirlys Richards, was the greatest find. I absolutely loved reading the true stories of the titular Walmajarri sisters – Ngarta and Jukuna – who remained in the desert in the 1960s and grew up living a traditional life according to their culture, when most Walmajarri people had already left the desert and moved onto the expanding pastoral cattle stations.

Some Walmajarri were enticed by the idea of staying with their family, wanting to remain close to relations and loved ones who had moved to the stations; others couldn’t reasonably stay in the desert any longer, now that the ancient and intricate system of trading, marriage, care for Country and communication of the desert people had been so disrupted by the new settlers. Others still were forced off their ancestral lands, chased down or cajoled, picked up in trucks and bought to the stations to work for a thriving cattle industry. These Aboriginal people, who came from all over the Kimberley region and inner deserts, weren’t paid – they were given rations, food and blankets, in return for hard, back-breaking labour. Meanwhile, the station owner’s pockets grew deep and heavy with the riches they were gaining, all from a people whose labour was essentially indentured slavery. You can learn more about the impact of stolen wages here.

But Two Sisters begins far away from all that noise. Ngarta and Jukuna were already old women themselves when they recounted their stories to non-Indigenous linguists, Eirlys Richards and Joyce Hudson, who came to Fitzroy Crossing community to learn Walmajarri and write a Walmajarri dictionary, recording the language before its last fluent speakers passed on. Later, the stories were told to prolific non-Indigenous writer Pat Lowe, who also lived in the desert for many years. With this context in mind, Two Sisters is an autobiographical retelling in both English and Walmajarri – and possibly the first autobiography written in an Aboriginal language. It is not just an act of storytelling, but an act also of language revival, remembering, and ownership.

We start in the desert, with a small Walmajarri family just living. Hunting, yarning, learning from the old people – as has been the custom for tens of thousands of years, as far back as memory goes. Ngarta recounts travelling from jila to jila, waterhole to waterhole, with her beloved grandmother, two mothers, father and siblings, including her older sister Jukuna. The family’s story is consumed by survival, the daily concern for everyone being to find food and water; but this is also primarily a human story, one anyone can relate to. There is sibling rivalry between sisters; grief and loss in the face of sudden death; feeling close to your grandmother who teaches the most important life lessons; and the fear of newcomers, change and disruption.

This disruption comes in the face of a cruel band of brothers who, like Ngarta’s family, have stayed behind in the desert while the other Walmajarri have moved to the stations. But unlike Ngarta’s family, these brothers are terrorising the Aboriginal people who chose to remain in the desert, and who without the protection of other tribes, can easily pick off the weak and vulnerable, and steal young women for their own.

Ngarta’s story is one of survival, empathy, and bravery in the face of violent, sadistic men. Ultimately, her isolation and vulnerability lead her to the kartiyas (whitefellas) on the station, where she is reunited with her sister Jukuna. Crying tears of joy and pain, Jukuna embraces the woman she thought had died long ago out there in the desert. Jukuna then tells her story, in her own words.

Jukuna was married young to her promised one, as is the way, and left her little sister Ngarta behind. Her husband and new family were soon encouraged into the station life as the demand for cheap (almost free) labour increased. She was introduced to a strange new kartiya world: one with the influence of alcohol on her men, long hours of domestic work, losing loved ones to unfamiliar diseases, and ultimately finding a Christian God, who she embraced fully and followed for the rest of her days.

My heart ached, leapt, and wondered in awe at different moments in their journeys, and I took great pleasure in seeing long pages full of beautiful Walmajarri, which I tried to read aloud (and probably made a fool of myself), letting the language fill the air around me. It is a wonderful thing to see the language root itself in an ancient past while proudly asserting its own aliveness and contemporary nature today.

Ngarta and Jukuna took different paths in the beginning of their lives, and where there is crossover in their early childhood in particular, their perspectives on events differ in some ways. Yet, their voices still manage to come together as one, speaking from a collective lens that Waanyi author Alexis Wright posits is shared by many Indigenous storytellers.

In Wright’s essay, ‘The Ancient Library and a Self-Governing Literature (2019)’, she writes that Aboriginal authors understand stories as involving all times, all realities, ‘the ancient and the new’, and embracing imagination. She reflects that this way of viewing the world influenced her writing for her novel ‘Tracker’, where she abandoned a western literature style of biography to instead use collective memoir storytelling that included decision-making from a wide variety of community members. In this way, everyone had a chance to share their story, and all viewpoints were considered valid. It is what Wright calls ‘the long vision’ and is tied to Aboriginal storytelling practices that are re-generative and interconnected, seeking to both share old ideas and support new visions.

Two Sisters reflects this same way of storytelling, told from two women’s points of view, neither one given the full embrace of fact, but rather flowing comfortably in subjectivity and shared remembering. With one eye on the past, looking at their personal histories, Ngarta and Jukuna also hold one eye on the future – towards their children and descendants, who will learn so much from their sharing of stories and language.

I never knew Ngarta and Jukuna, but on a personal note, I grew up with Pat Lowe, Eirlys Richards and Joyce Hudson in Broome. They are icons, absolute legends of the Kimberley. As a young girl, however, I had no idea of all this decades-spanning work they had done with these elders in communities, helping them to write down their language. It was a pleasure to discover Two Sisters and unravel some of the wonderful work in language restoration that has been happening in the Kimberley, and which continues to happen today.

To speak language is to stand strong in your culture and pay respect to your culture. This is what truly makes Two Sisters a book more precious than most.

~

Question for your next book club: What differences do you find when you compare Ngarta and Jukuna’s stories? What similarities are there in their experiences? How do you think these have impacted their identities and lives growing up?

Note: If you’re interested in reading more regular book reviews for books by Aboriginal writers, I highly recommend you follow @blackfulla_bookclub on Instagram, they are fantastic!